How To Pass The CASI Level 4: Evolution Of A Lesson Plan

I’d like to start out with a little note on my goal for this article, as just like any good lesson plan, if you aren’t sure where you’re heading it’s almost impossible to get there.

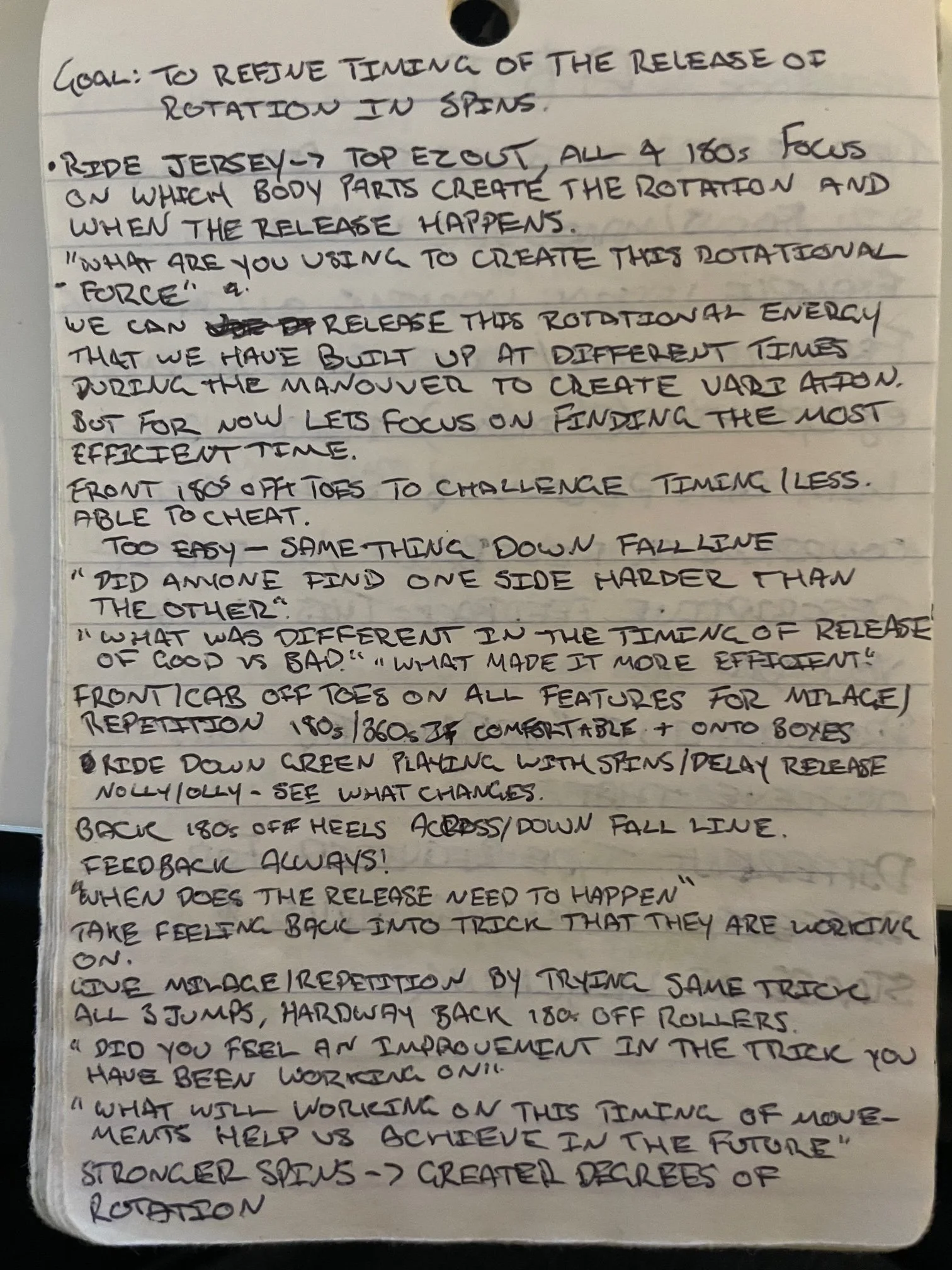

In writing my last trip down memory lane/advice column/auto biographical recount of my repeated failure to pass the Level 4, I found myself digging through old notebooks looking at lesson plan ideas. What was immediately apparent and sparked the idea behind this article was how different they were from the start of my Level 4 journey to the end.

As instructors, particularly those training for higher certifications, we are told to write lesson plans. How to do this (outside of filling in those generic templates in the course book) is left up to you.

My hope is that through sharing in the evolution of five years of notebook lessons it might give you some tools to plan high end sessions with confidence and adaptability.

It genuinely makes me laugh to think of myself getting ready for my first teaching exam. Looking back at the plans I had, I feel for that kid. Despite all the hard work and preparation, I really hadn’t set myself up for success. At the time, you would be assigned a skill focus and pedagogy focus the night before your exam.

I, being extremely prepared, had come up with a solid plan for any possible outcome! Notebooks full of ideas.

At least a solid idea…for a plan…for each possible outcome.

Lets call them ideas for how you might run a session on each skill.

The spark notes if you will.

You might say…the bare minimum of what you would want to start with. Before actually coming up with some kind of plan.

I was ready.

It is absolutely amazing to me that I made it through these exams feeling like some kind of snowboard instructing prodigy, putting forth some truly inspiring ideas to stimulate the minds of these career snowboard professionals. The moment 15 minutes into my first pedagogy session where I explained how I was finished and had nothing more to add. Or the fact that I had spent an hour teaching level 4 candidates what counter rotation is. Should have both been hints I was missing the boat.

It would certainly have helped temper the soul crushing experience of failing everything for the first time.

What this taught me regarding my lesson plans was huge:

It is not enough to have an idea of what you may teach and a rough list of drills to help you get that idea across. You need the details. To know the kinds of questions that may arise. What you plan to say in your intro. Where you’re going with both terrain and skill development.

What you need, is to know the goal of your session. Makes sense really. What hope do we have of helping people achieve improvement if we’re not sure what we are actually trying to achieve.

I now had a new plan for how to make a plan:

Step 1 - Refine the goal till it perfectly captures all you want to say while also using big words to make sure the evaluators can see you know a lot of them. For example this gem “How to control environmental pressures more efficiently through a more refined awareness of the muscle tension in our legs”

Step 2 - Write down everything you are going to say at each stage of the session so that you get across all the information with a nicely rehearsed speech.

Step 3 - Make sure to include every possible type of terrain and turn shape so as to cover all the possible ways the movement you chose can be used.

Step 4 - Start prepping for next years exam.

Although the goal for the sessions seemed clear in my head and despite making sure to use the terrain to its fullest, my plans didn’t allow for any real discussion or progression. By changing turn shape, style and terrain so much I basically restricted my students to only ever starting to feel what I was trying to convey, without any actual time to develop it.

The big lesson planning take away from round two of failing everything was: What ever it is you plan to work on, your ultimate goal should be to improve your students ability and/or understanding. A mind blowing revelation.

This is really where my lesson plans started to improve and look more like mediocre level 4 sessions and less like decent level 3 ones. My focus changed. All the feedback so far had been along the lines of: “Good idea. Started well but too wordy. Took a while to get going. Never really developed/progressed.” Yet I had just passed my riding. I could do the thing, I just didn’t know enough about what I was trying to explain.

A mentor of mine once said “Passing the level 4 is easy. You just have to know everything about all of it.”

While this now makes me laugh as years later I’m still learning, it did change the way I viewed my training, particularly how I wanted to develop a lesson plan. Instead of spending my time writing a script, I focused on three things:

Pick a skill and come up with as many lesson ideas as possible.

Pick a thing you do on the snowboard and break down each movement required to make it happen.

Pick a teaching skill and list all the ways its helpful to you or students.

This is where I should have started. I had spent the first three years focused on how to pass the exam. I should have spent them focused on learning more about the sport I loved and how to share it with others.

(I have notes like these for every skill and environment I could think of)

Having spent the time to dig deeper into the aspects of teaching and riding that most interested me, I started to get it, kind of. I had focused my goals on passing the teach and ended up walking away with the pedagogy component instead. The success came from a few things really. I chose a topic I was interested in, kept the lesson structure and concept simple, and planned to collaborate with my group to drive the lesson forward.

The biggest trap I see trainers regularly falling into when working with high level athletes or instructors is that they are still trying to teach them something. Instead of a discussion it’s a lecture. If you want to truly improve skills at this level, you need to work with your students, find out what they can do already, and have them practice ways to improve it.

I have lost the lesson plan I did for this session because, I believe, it was on a napkin. Which already tells you a lot. By the end of the session they were to have a better understanding of how to teach their students to self analyse. I picked the park as the environment for its obvious outcomes and clear cause and effect. What maneuver, trick or features we used are irrelevant. I let the group define the challenge level, gave them the freedom to try things and made them practice working backwards from the outcome of how the maneuver felt to find the cause of the issue.

On the flip side the lesson plan for the teaching exam was both detailed in its content and timings as well as potential feedback each student would need. What I failed to do was be prepared for a split in ability levels. I couldn’t process how to keep the group engaged while also creating buy in for the one that wasn’t getting it.

The screen play I had written looked good on paper yet it didn’t allow room for adaptation. Literally anything can make you have to change your plans mid way through a lesson. This happens daily as instructors. Unfortunately for those of us determined to test our skills in high end certification exams, these little things suddenly become huge obstacles.

In nine level 4 exam lessons I’ve been rattled by: Students not getting it. Students getting it too quickly. Bumps randomly groomed the night before. 30cm just in time for my carving session. Concrete park conditions. Huge splits. Language barriers and even students in hard-boots.

All of these problems had solutions, I just wasn’t ready to see them. Adaptability in good coaching isn’t about planning every outcome or even an air-tight schedule of events. It’s about having confidence in the goal and the understanding to help guide your students to reach it.

The last lesson plan I wrote on the path to the level 4 was arguably the simplest. The super technical high level goal? Ride smoother in bumpy terrain. How? Do an Ollie. A versatile building block progression to cater to the group in front of me and some common issues I may see to help with the feedback. The part of the plan with the most detail, what to say in the introduction, was ironically where the evaluators saw the most room for improvement “explanations too wordy/long at the start of the lesson.”

It might seem easy to say “don’t over think it, don’t over plan, let the lesson progress organically.” But in reality this is only made possible by the work done beforehand:

Know everything about all of it - Do the work. You want to be able to run a bumps lesson? Write down every aspect of turning in the bumps you can think of. What do you know about pressure and how it relates to board performance? What are the different ways we can create or release pressure? How do each of these effect performance? What are all the different ways we can use pushing on our back foot to change our riding? Front foot? Can we achieve the same thing using a different skill, or even the bumps themselves?

This is where good lessons start.

Plan to collaborate - You are not the only person in your lesson. You aren’t even the most important person in the lesson. You are a facilitator. Your job is to use your knowledge and help your peers build on the skill-set they already have. Let them help you, if the lesson feels like it should go a certain way and that way isn’t in your plan, you better have a really good reason for ignoring the progression that’s happening organically in order to do something different.

Adaptability is key - You can’t collaborate and you definitely can’t be adaptable if you’ve not done the work. No lesson will ever go exactly how you planned. True adaptability comes when the questions that may otherwise derail a lesson instead provide a wonderful opportunity for real progression. If your lesson plan does not allow for adaptability and you need everything to go exactly to plan, chances are, you’ve already failed.

What does that even mean - The goal of your session is your session. If it’s not clear to you, what hope do your students have. Take the time to work out exactly where you’re heading, before you start moving.

If you know your stuff, have a clear achievable goal and a progression that allows for adaptability, all those other teaching skills will finally have some room to shine.

Hopefully this helps in some way.